Hello! I'm Jenn, UX designer and artist. I'm an expert in designing software for scientists. I've spent

my ten-thousand+ hours working on tools to enable scientific research. I care a lot about open

education, and

creating accessible digital infrastructure.

You can learn more about my design process by listening to my ADASS talk,

Empowering Science with Good Design.

Since 2017 I’ve led UX design at

MAST, a NASA data archive for

space telescope missions like Hubble and JWST. I’ve given a handful of talks and my work has been highlighted in some exciting and fun places.

I also paint, write, do user research, create logos, animations—if there's an art thing I've probably

tried it once.

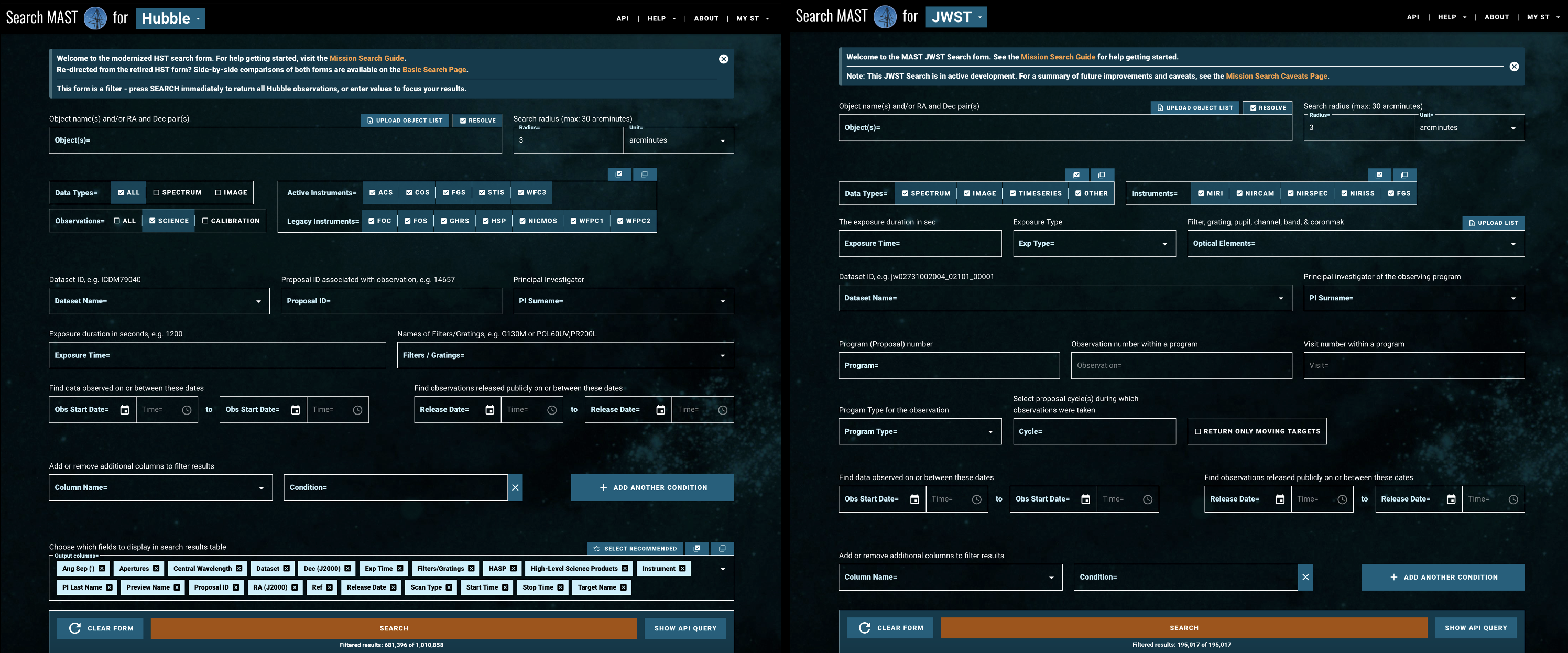

I am the first designer to work at MAST, a data archive for NASA space telescopes. The archive was

composed of many search forms that looked like they were built in the 90’s by scientists. (They

were, and they were!) These forms had different design patterns, both visually and for completing

tasks—there was much unnecessary complexity. Science workflows are often complex, but they shouldn’t

be made even more complex!

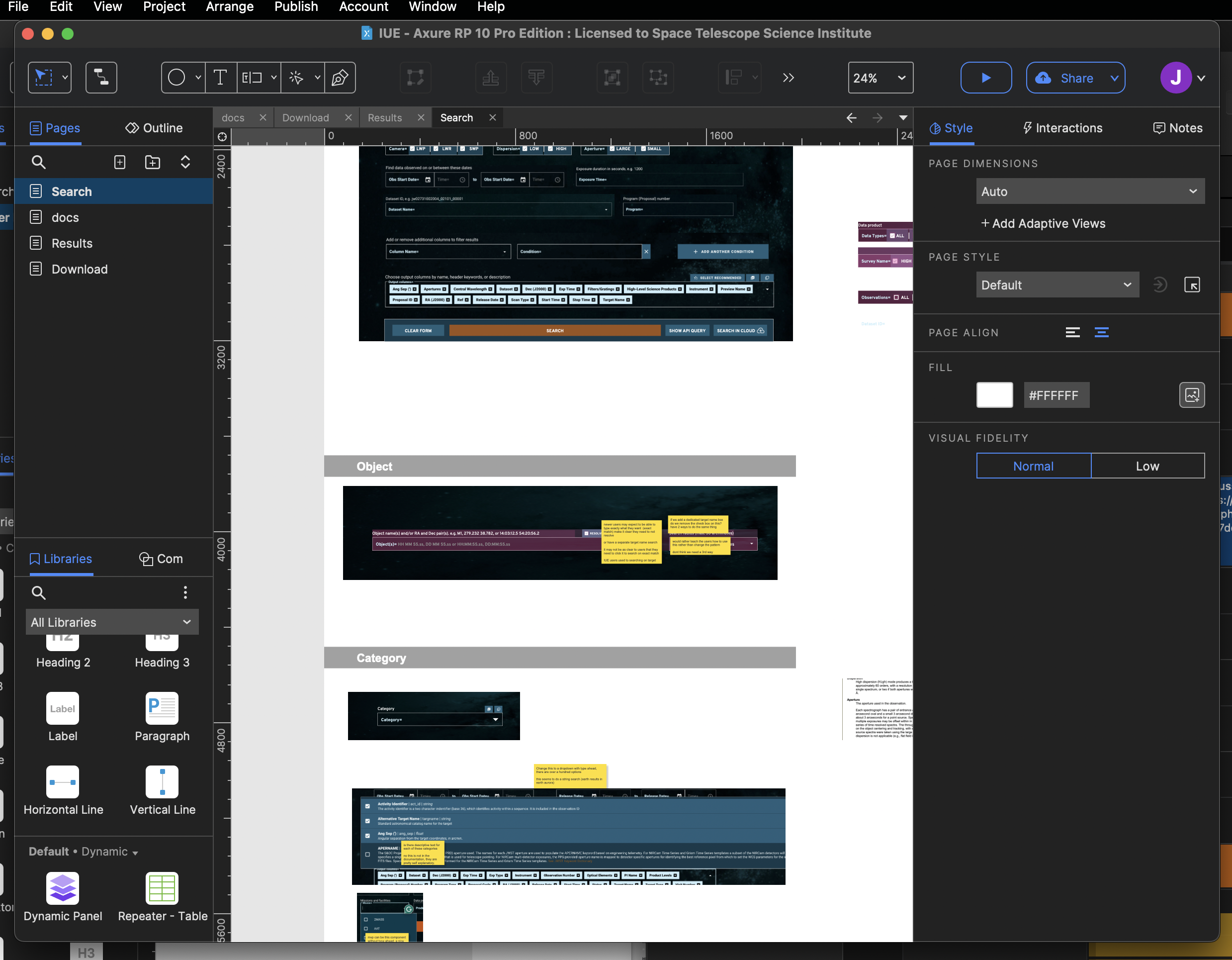

Over several years, I have designed a system of cohesive components to use across MAST’s many

searches. I have established common workflows that are repeated in different contexts. Now, MAST

searches are a part of an interconnected system. Scientists who are familiar with one can easily

swap to another, making them easier to learn and use. I continue to expand and interconnect this

system as new telescope missions are added to our archive.

Over several years, I have designed a system of cohesive components to use across MAST’s many

searches. I have established common workflows that are repeated in different contexts. Now, MAST

searches are a part of an interconnected system. Scientists who are familiar with one can easily

swap to another, making them easier to learn and use. I continue to expand and interconnect this

system as new telescope missions are added to our archive.

This has been a complex, multi-year project, involving many stakeholders: developers, project

scientists of different backgrounds, mission leads, and the astronomers who use MAST to conduct

their research.

This has been a complex, multi-year project, involving many stakeholders: developers, project

scientists of different backgrounds, mission leads, and the astronomers who use MAST to conduct

their research.

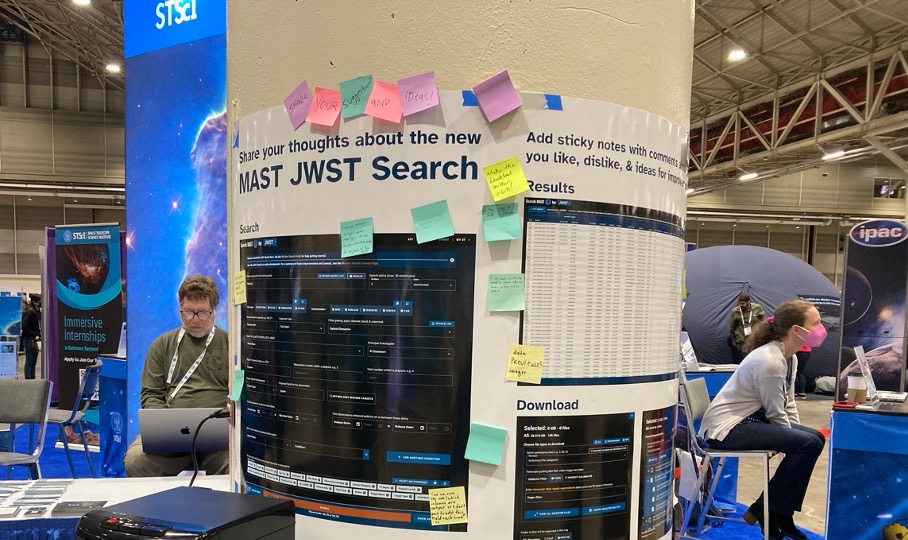

I have stayed focused on our core users: research astronomers. I have led design workshops and gone through iterative rounds of feedback with scientists. I've run usability tests, created surveys, reviewed helpdesk requests, and even tried experimental methods like interactive conference posters.

I have stayed focused on our core users: research astronomers. I have led design workshops and gone through iterative rounds of feedback with scientists. I've run usability tests, created surveys, reviewed helpdesk requests, and even tried experimental methods like interactive conference posters.

Jdaviz is astronomical data analysis and visualization tools based on the Jupyter platform. These

add a UI interactive layer to computing notebooks. They are designed to work within a Jupyter

notebook cell, as a standalone desktop application, or as embedded windows within a website.

For this project I have consulted with the team of developers and scientists on adding features and

streamlining existing features. I have designed logos and icons and led usability feedback sessions.

I've been working on my grad degree for 8 years, 2018 to 2025. Across the years, classes and projects, a theme has emerged within my work: community driven design. How does the built world create community? I decided to take my collection of related writing and projects and turn them into a series of zines called Blocks. This is my mini capstone project, a culmination of the work I've done while in grad-school.

These writings are all on topics related to place, home, community, and neighborhoods. They follow the same visual language, sharing iconography spacing, typography.

They will be available to purchase in print or to read online for free on substack.

Jupyter Notebooks play a central role in modern data science workflows. Despite their importance,

these notebooks are inaccessible to people who rely on assistive

technology like screenreaders. Impacted users must find extreme workarounds or give up using them entirely. Students

with disabilities have reported leaving their field once they learn their chosen career’s

foundational tools are inaccessible to them. I led a multidisciplinary team to try to solve this problem.

I gathered a team of people with

different backgrounds and skills. We wrote a killer grant proposal and was awarded and

administered a 6-figure grant. Notebook accessibility is a super thorny problem and we did not solve

it, but we did make progress!

My part of the project was collaboratively writing and conducting

usability tests with people who use assistive technology. We did two rounds of usability testing on

Content types, structure and navigation.

The scripts and results are all publicly available.

Based on the feedback we gathered, our developers experimented with an improved notebook html

output. Our lead developer Tony Fast has continued working on this in his project nbconvert-a11y. We also established best practices for writing notebooks accessibly. We condensed this

information into an accessibility checklist that people building notebooks can reference.

As part of this grant we organized public events: Accessible Notebook Hackathon and Day of

Accessibility, and presented our results at Jupytercon 2023 to try to gain awareness and get more

people working on this problem.

Astronify is a python package that sonifies--turns to sound--astronomical data. I was a core member of a small team awarded a grant to pursue this experimental work.

I led the usability testing of the sonifications. This was an adventure through uncharted jungle,

exploring user-patterns that aren’t well established. We focused on how

sonification could be useful for scientific research—they needed to be interactive and convey

meaning that could be used by a scientist, not simply tell a story. This is fundamentally different than a curated

sonification for the general public. I worked with GLAS education to connect with blind and low

vision technologists who I met in one-on-one sessions to gather feedback. I also used gamified surveys to

gather asyncerous feedback. People play a game trying to identify meanings within

sonifications, and based on their answers, we learned if the information in the sonification was

discernable.

I also led community outreach. I created a series of videos explaining sonification and astronomy concepts to

an amateur audience. For these videos I wrote and recorded the script, edited the recordings, came

up with a visual language that would be the most visible for low vision audience, and animated the

videos. The videos were featured as a learning resource on the Perkins School for the Blind website. I connected with the NPR show Out of the Blocks which featured

Astronify. I presented the an astronify gameshow at a sonification festival and conferences

internationally.

For the capstone class of my Grad

degree, we were randomly grouped and paired with a company. My teammates were Jess Robey and Michael

Davenport and we were paired with Alpha Brothers is a trucking company located in Baltimore, MD.

I'll be honest, a trucking company was the most difficult assignment. Us three designers had no knowledge of logistics business, and we couldn't simply come up with a cute branding scheme. We needed to dig into the problems facing the industry—hiring and retention. We interviewed the owner for several hours just to wrap our brains around the problems facing his business.

I'll be honest, a trucking company was the most difficult assignment. Us three designers had no knowledge of logistics business, and we couldn't simply come up with a cute branding scheme. We needed to dig into the problems facing the industry—hiring and retention. We interviewed the owner for several hours just to wrap our brains around the problems facing his business.

And then we got to work. We analyzed the regional competition, created a visual and written voice, planned a hiring campaign, and executed several example billboards, commercials, and videos.

I collaborated on several iterations of the logo helping to balance the colors, and I came up with the tire track branding using the logo shape.

My key contributions were in writing. I did the bulk of establishing brand voice, distilling what we learned from our interview with the owner into a set of core values and phrases.

My key contributions were in writing. I did the bulk of establishing brand voice, distilling what we learned from our interview with the owner into a set of core values and phrases.

I rewrote the scripts for our radio and video commercials, adding the brands voice.

I rewrote the scripts for our radio and video commercials, adding the brands voice.

The class ended with a design competition of which team's design solution best met the needs of the company. We won!

The class ended with a design competition of which team's design solution best met the needs of the company. We won!

I collaborated with Iota School to organize this event. We gathered people working in science and tech to engage with the challenges around making science and tech inclusive. Through a series of talks and hands on learning activities.

Attendees learned about accessibility challenges in STEM, and will left prepared to act as

accessibility advocates in their work. All talks and slides are publicly available.

Our keynote was Joshua Miele: a MacArthur fellow and leader in adaptive technology design. Science

writers talked about best practices in astronomy alt text, the notebooks for all team

spoke about Jupyter Notebook accessibility, and Dr Scott Fleming spoke about data sonification.

Dr Patrick Smyth of Iota School a hands-on workshop to learn the fundamentals of using screen readers.

We had interactive tactile exhibits on display. We were pleased to welcome a diverse audience

including a large cohort from the Baltimore School for the Blind.

I collaborated with Iota School to organize this interactive hack event for Jupyter Notebook authors. We started with a talk explaining accessibility issues with notebooks—they don't read well on screenreaders—and practical tips for making notebooks more accessible. Then, atendees spent an hour applying what they learned in a notebook they were working on. We ended by gathering as a group and sharing our results.

I was invited to run a similar event at Rubin Observatory.

I envisioned, found funding, and organized this paid internship program for high school artists.

Each student creates art inspired by astronomy data in the medium of their choice. We had students

create paintings, sculptures, music, animations, and augmented reality apps. I collaborated with

colleagues to run the program.

In 2023 We hired a cohort of 12 interns from Baltimore to create art inspired by astronomy data. The program was 6-weeks and the interns worked 10-15 hours a week. We met in

person at Space Telescope Science Institute once a week for 2.5 hours. Alongside time creating

artworks, the students met MAST scientists, wrote a weekly progress journal, participated in

educational talks, and visited James Webb mission control. We ended with a gallery show at STScI

which was widely attended and well enjoyed.

In 2021 We hired students to create art inspired by space sonification that was accessible by a

blind audience. We met by video chat for 6 weeks. The student artists were both blind and sighted

themselves—so we had a lot of interesting discussions about accessibility and art.

In November 2022, I attended an artist residency in Svalbard where I discovered the visceral joy of

swimming in freezing water. After returning to Baltimore, I struggled with how to keep my connection

with wild waters. This led me to jump into the contaminated (but now considered safe to recreate in) waters of the Baltimore Harbor.

In my Writing Baltimore class at Ubalt, I explored these experiences in two yet-to-be-published

personal essays and this short film, Swimming in the Arctic. I presented this film at the Small Doll

Film Festival on the theme of fear in 2024.

Using historic census data from 1790 - 2020, I explored data Baltimore population through

sonification. The final recording and the notebook I used to generate the files are available on

Github.

In Baltimore there is palpable tension between the city and the county. Even the name. Baltimore

county refers to itself as Baltimore and to the city as Baltimore city. City people call the city

Baltimore and Baltimore County is just the county. (With a air of distaste on both sides) They fight

over the name Baltimore itself.

I started by visualizing the information on a graph using Excel to find out if I could see the story

before I listened for one. I only had data until 2010, so I found the most recent census to complete

the set. It was challenging to find that, for a minute I thought I would have to come up with the

number by adding all the populations of different jurisdictions in the county, but luckily

I found the data I was looking for.

I used Astronify to

generate the sonifications. It is meant to be used with lightcurves, but I knew it would work as

long as I had a list of numbers.

I created a Jupyter notebook and pulled in the census data I created a table that Astronify could

use to sonify. Then I generated separate sonifications representing the city and the county’s

population data. I could hear something that I hadn’t noticed when inspecting the data visually.

There were 3 main sections of differing trends.

Since the sonification by itself is not self-explanatory, I decided to write a script and use that

as an opportunity to focus on those 3 section trends. I recorded a few takes of myself reading the

script. Then edited the recording and sonification together in Audacity.

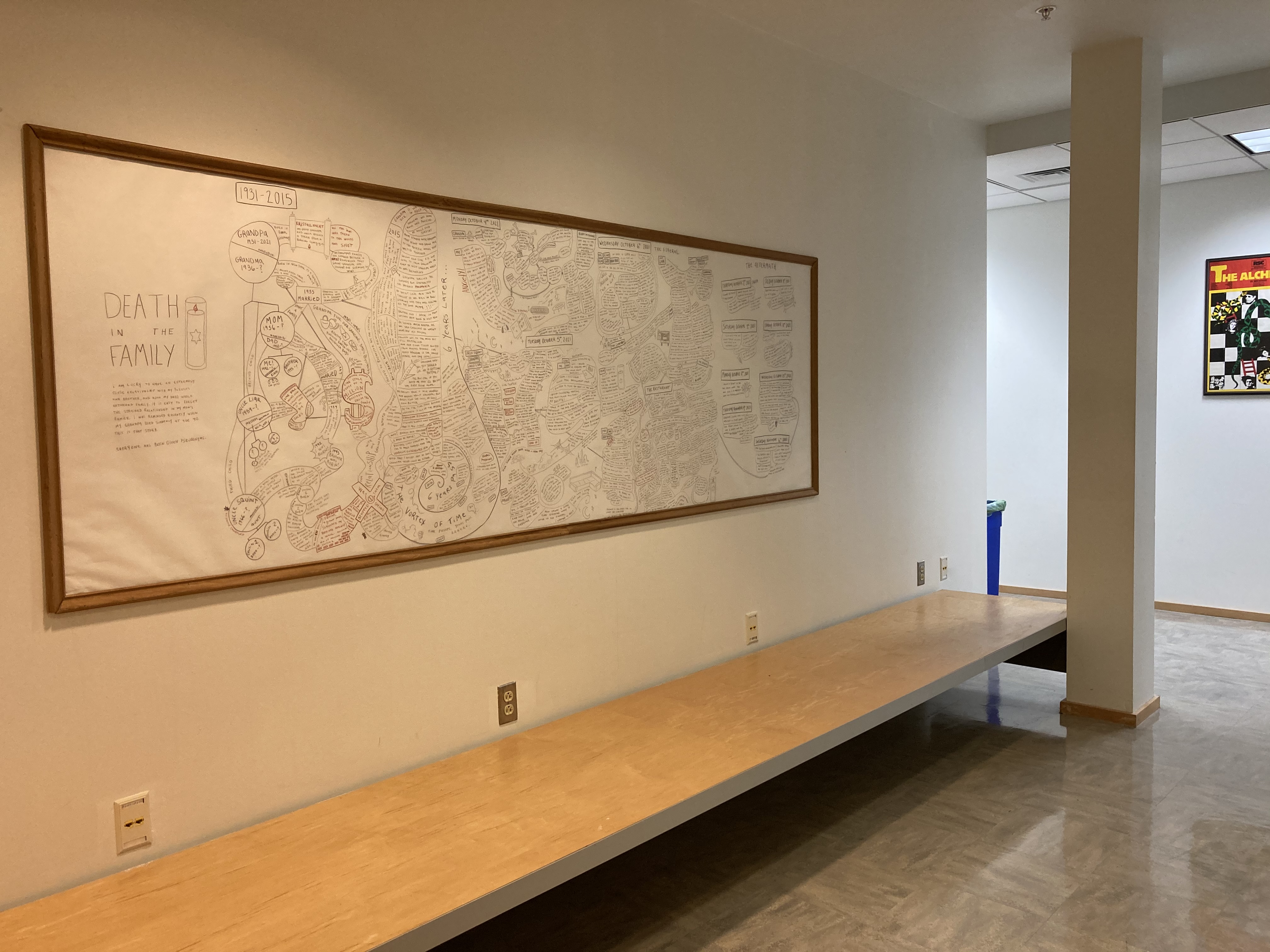

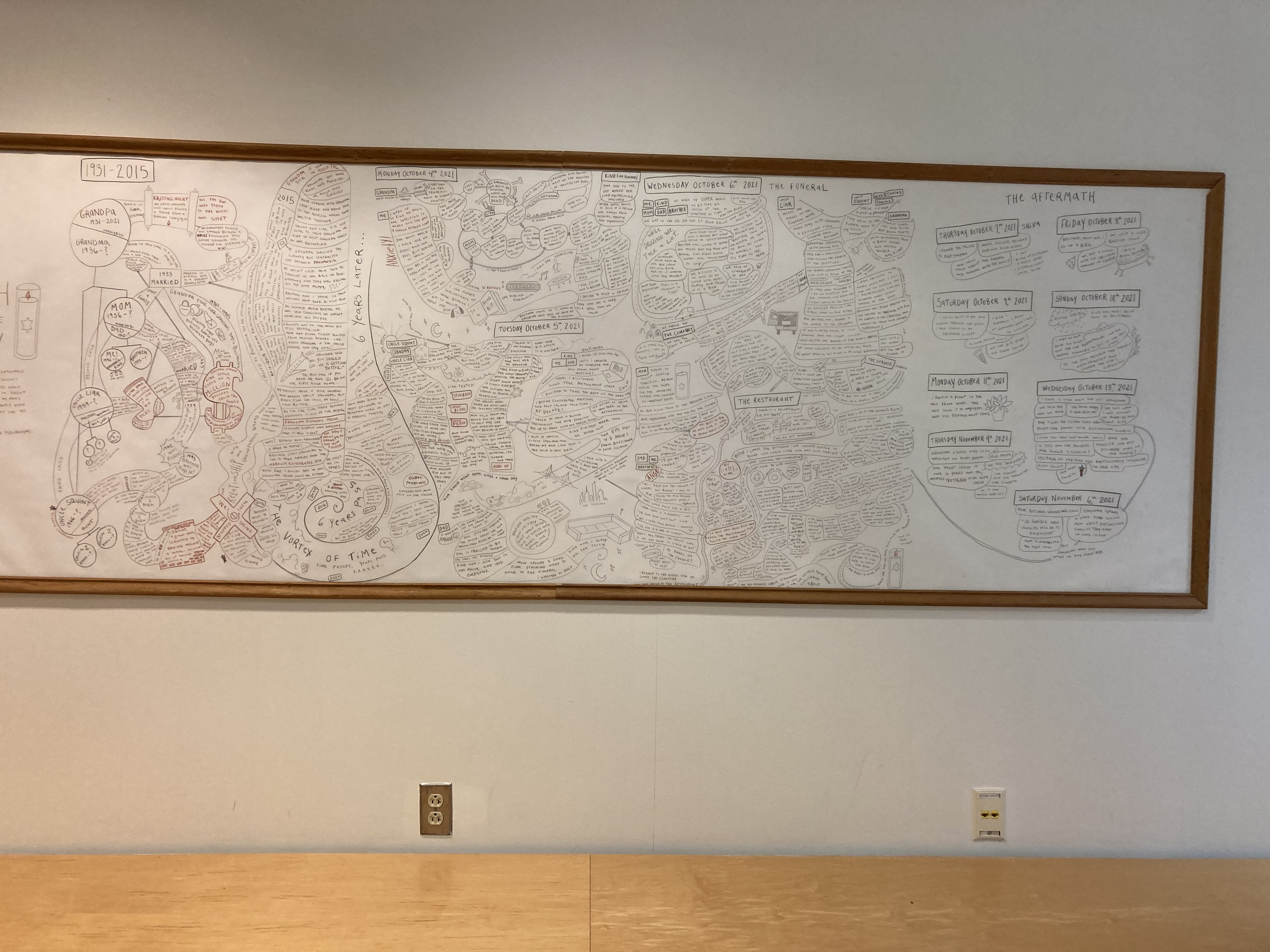

I drew this timeline with color pencil on a translucent roll of paper measuring 8 feet wide by 3

feet tall. It is the largest art piece I've created.

This piece was created for a Typography class at UBalt. I borrowed the concept and visual language

from the artist

Ward Shelley.

Rather than following a subject through history like Shelley, I followed myself through a period of

time. My aim was to capture the experience of my grandfather's death, and connect it with the wider

context of my family history. This is a memoir of sorts, but in timeline form. I share interesting

pieces of data (weather, location, mood, etc) and intersperse with moments of narrative. This

information is conveyed with a mixture of graphing, illustration, and writing. It is read

horizontally from left to right.

This piece was created for a Typography class at UBalt. I borrowed the concept and visual language

from the artist

Ward Shelley.

Rather than following a subject through history like Shelley, I followed myself through a period of

time. My aim was to capture the experience of my grandfather's death, and connect it with the wider

context of my family history. This is a memoir of sorts, but in timeline form. I share interesting

pieces of data (weather, location, mood, etc) and intersperse with moments of narrative. This

information is conveyed with a mixture of graphing, illustration, and writing. It is read

horizontally from left to right.

For 5 years, A Death in the Family was exhibited in the UBalt Liberal Arts Building gallery. I mounted it to the wall, framing it with molding. I also produced an accordion book for those unable to visit the exhibit.

For 5 years, A Death in the Family was exhibited in the UBalt Liberal Arts Building gallery. I mounted it to the wall, framing it with molding. I also produced an accordion book for those unable to visit the exhibit.

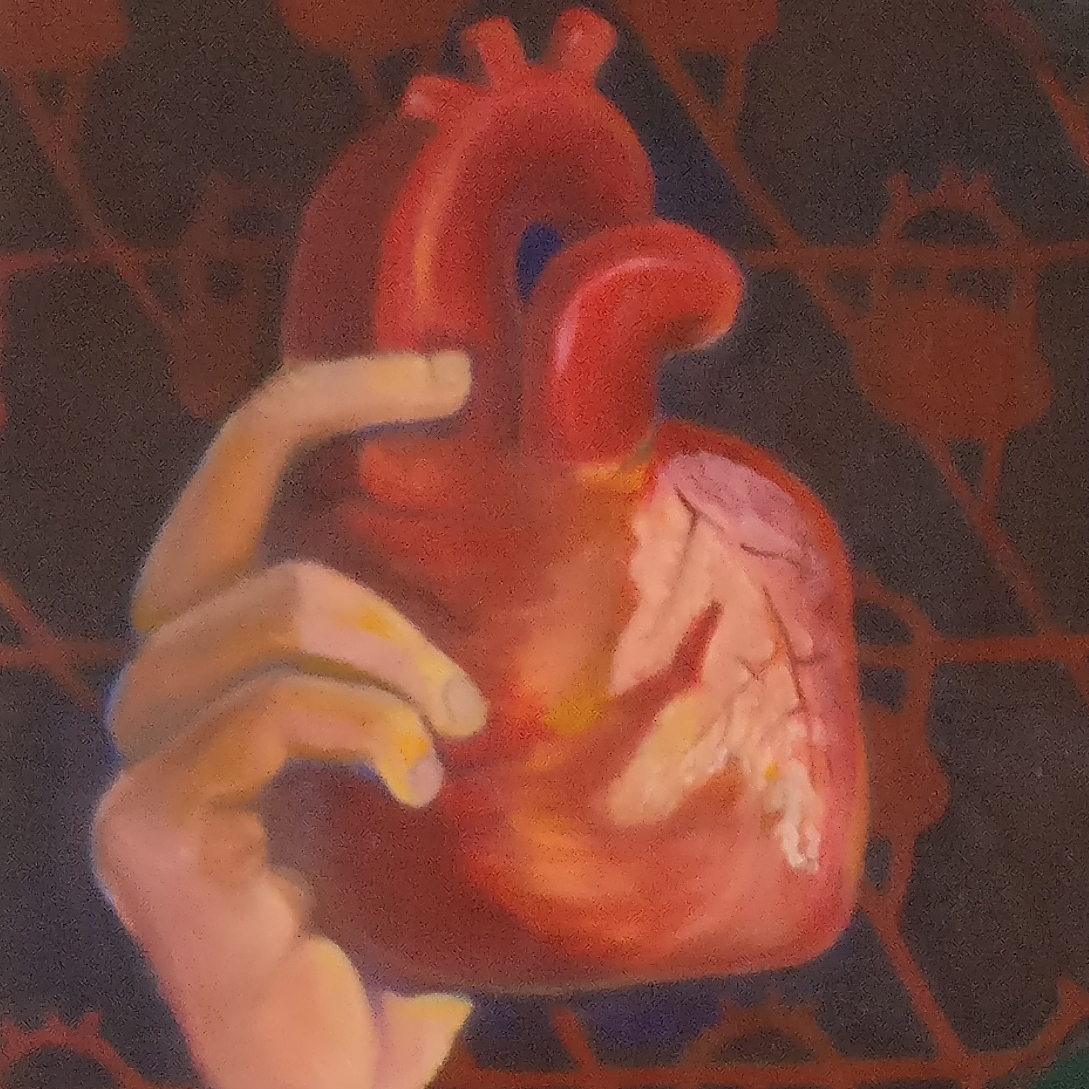

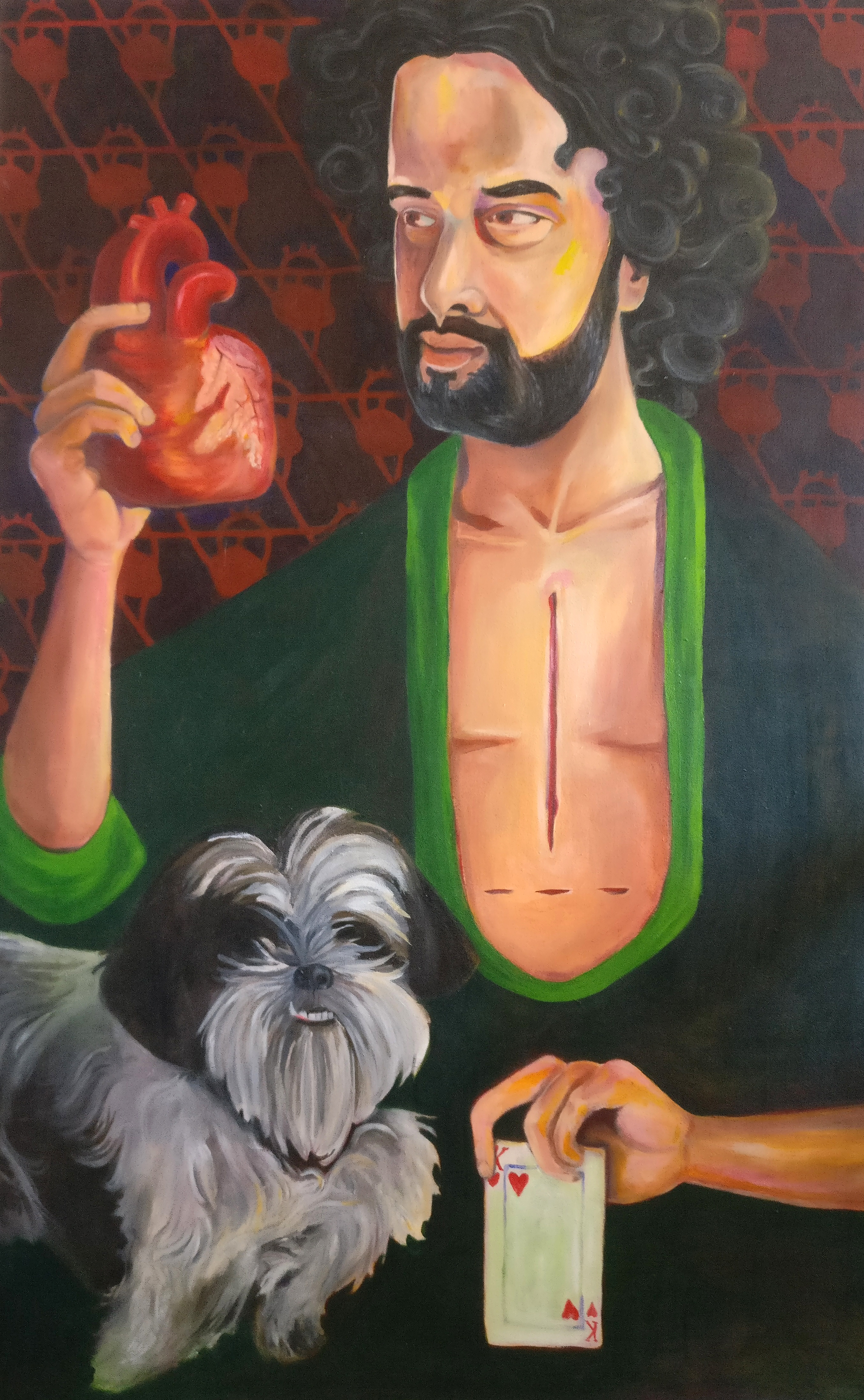

King of Hearts is an acrylic painting on stretched canvas, 3 feet wide by 4 feet tall. I painted it as part of my grad classes at Ubalt following my spouse's heart surgery. This painting has a lot more intentional, personal symbolism than most paintings I do. I also had the fascinating experience of hearing its symbols analyzed by a bunch of design grad students. This taught me a LOT about 'meaning' in art.

The meaning of artwork is not static. Images have layers of rhetorical and cultural significance that are read differently from viewer to viewer. Our personal perspective limits an artist so that they can never be fully aware of all interpretations of their work. One explanation of artwork is not necessarily more correct than another. A viewer's personal relationship with art has value separate from the artist's intention. Imagery that is intensely emotional to the artist might mean nothing to the viewer. A viewer may be deeply touched in a way an artist could not have predicted.

Understanding an artist’s intent can be important when analyzing a piece, it is not necessarily what will matter most to the audience.

King of Hearts’ composition intentionally alludes to Western religious and royal portraits. Other grad students interpreted this as I intended describing the image as “byzantine, catholic aesthetic,” or “like religious art.”

The playing card was another recognizable cultural symbol. The grad students noticed my comparison of the figure with the card in his hand. “The card is missing its portrait; the man becomes a stand in.” This interpretation intertextually combines with the title King of Hearts to solidify part of the painting’s intended meaning.

King of Hearts has a layer of symbology that relies on familiarity with the medical field. For instance, knowledge of the circulatory system is required to read the pattern being depicted on the wallpaper. As I shared the painting with a design students, comments such as “what’s the background?” “is it a teapot?” exemplify how symbols can't be interpreted as intended without knowledge of how to read them. A home-care nurse and medical illustrator who viewed the painting immediately focused on the wallpaper and excitedly recognized the pattern as the circulatory system.

Similarly, recognition of the scars as surgical require familiarity with heart surgery. The medical professionals recognized the scar and asked specific follow up questions about valve repair. The design students interpreted the scar as a metaphor for being broken, or as emotional trauma. For those focused on the cultural signifiers rather than medical ones, King of Hearts is an honorific painting of a man with emotional baggage.

A small group of family and friends have a personal connection to this painting. This is a real person. He's not a metaphor. For those who paced the hospital waiting room during the surgery, these symbols are not symbols – they are visual representations of an impactful experience. The scar is not a metaphorical symbol of being broken, it is the physical manifestation of a major medical ordeal. When my mother-in-law saw this painting for the first time, she cried.

By compositionally emphasizing the scar and proudly displaying it as decoration, my goal was to honor my partner's experience.